Spending years in Vietnam during the war can take its tole, even if you are not a combat soldier. While there, I tried to come back to reality every six months by taking a brief R&R. Usually I went to Hawaii and once, I returned home to Australia. But this particular time I decided to take my break in Tokyo. After all, I had lived in Japan a few years earlier when I was working as an exotic dancer. I enjoyed Japan and I genuinely liked the polite people.

The Otani Hotel was the newest and most modern in Tokyo that year. Staying there was a nice contrast from the army bunks I usually slept on in Vietnam.

It was my first morning when I stepped out of the revolving doors into the warm sunshine. At the kerb, in front of the hotel, I spotted a young American in uniform. He was bending over beside a Mitsubishi cab.

“The Ueno Railway station,” he was saying “I want to go to the Ueno railway station…you know, train. Train.” He made a moving motion with his hand as the nonplussed driver shook his head and inhaled noisily.

“Train, train…you take me?”

I walked over to the cab and translated, causing a large grin to spread over the cabbies face while revealing two gold teeth.

“The young soldier turned gratefully to me. “Thank…

“Look out!” I warned, grabbing his arm and pulling him back from the cab door which had automatically swung open.

“What?”

“These big Japanese cabs have automatic doors. You have to watch they don’t smash you in the stomach.”

“I seem out of my depth here, Ma’am.” He replied. “I wish I spoke Japanese like you. Thanks for helping.”

The Cabbie was twitching impatiently in his seat, anxious to get going. Indeed, the soldier did look lost – so young and innocent in his freshly starched uniform. He had a boyish appeal which aroused my sympathy.

“I tell you what. I’ve got nothing better to do, would you like me to accompany you and keep you out of trouble?”

His eyes lit up. “Would you? That would be just great. I’m heading to a museum I’ve heard about and I was worrying how I would find the correct train.”

“Then jump in before this fellow takes off and leaves us.” I was climbing in as I spoke and the American had barely settled beside me when the door slammed shut and the driver lurched the cab forward.

“My name is June,” I said. “What’s yours?”

“Woodrow Wilson Knapp” he replied, “But my friends call me Woody.”

“On R&R are you?” I asked, not recognizing any uniform insignia. “What unit are you with?”

“I’ve never set foot in Vietnam. I’m a pilot on the aircraft carrier the Oriskany. We patrol the Gulf of Tonkin. The closest I get to Vietnam is when I fly over it on missions.”

“Well it all has its danger although I’m sure your in-between times are much better than those of the grunts.”

“Do you mind me asking you what your accent is?” a warmness, as well as curiosity, had crept into his voice “And what do you know about the grunts?”

“I too am on R&R from Vietnam. I’ve been there a couple of years already.”

His eyebrows shot up. “Well, pardon me saying so Ma’am but you sure don’t look like any military personnel that I’ve yet met.”

“Probably not. I’m a booking agent, placing rock bands into the camps to entertain the troops.”

It was hard to miss the admiring glances he was now tossing my way. I silently acknowledged that I wasn’t the ‘norm’ that a young man would expect to meet while on R&R in Tokyo. And while he had immediately made a good impression on me, it was not one stirring instant lust. After all, I could tell he was a few years younger than me, who, at 28 had experienced pretty much all that life had to offer. His aura of innocence made me feel I wanted to take his hand. He was different from the men I usually met- kind of innocent and sweet – with a purity, which somehow, did not detract from his masculinity.

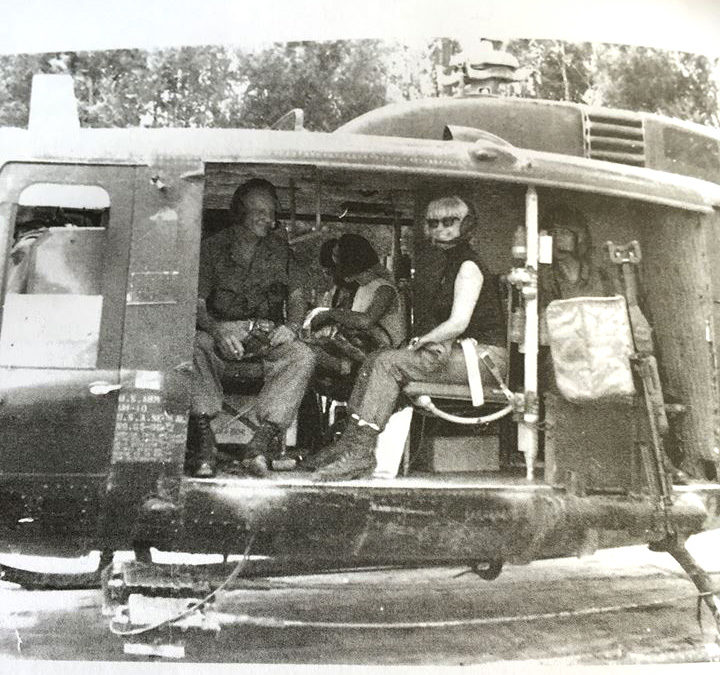

We spent a lovely day together. We laughed as we were shoved and jostled onto the Japanese trains which bulged with way too many passengers. We visited a hilltop look-out and Woody clowned for the camera as I took movies of him.

He invited me to join him and three of his pilot buddies later that night for dinner. They too were off the Oriskany and were staying at the Otani.

They were all young, early twenties. Fine young men.

I did not enjoy the evening. At one point they decided to drink a toast.

‘Let’s order a bottle of Mateus Rose,’ one suggested. They all agreed. ‘That was Marshall’s favorite drink. He was shot down last week, another KIA of ours,’ he somberly explained.

I did not want to join in the toast. Reluctantly I did and as I lifted the glass to my lips, a cold shiver ran up my spine.

After we left the dining room we headed for the elevator and watched the light as one descended to our level. It stopped and the door opened. A teenager ( or so he appeared) fell out into the foyer wearing a disheveled uniform. He staggered forward, mumbling incoherently, and bumped into me. Woody’s demeanor instantly changed.

“Straighten up soldier,” he barked. “You’re a disgrace to your uniform. If you are staying here, get back to your room and sleep it off.”

The drunken troop spluttered “Aw shit,” then tumbled back into the elevator.

I felt uncomfortable. “That was a bit harsh,Woody,” I said. “He is so young and we don’t know, he might have been out in the field yesterday and may have just seen his buddies killed. They have it really rough.”

“He represents America,” Woody ground out. “He’s in uniform in front of the Japanese. This is not a whorehouse. There’s no excuse.”

When I was alone later I thought about our opposing views. Grudgingly, I acknowledged that Woody was right…but I still had some sympathy for the young drunk.

We spent three glorious days and nights together before we parted – he for the ship and his war plane and me for the camps of war.

Woody’s letters soon started arriving. They were intimate letters, telling me about his life on the ship and recalling his days before that with his family. He spoke so fondly of his parents. His father was a top executive with Pan American Airlines. We learned about each other through the United States APO.

Then one day, I received a letter from him asking me would I marry him as soon as he got out of Vietnam. This was the last thing I expected. How to answer it? How did I feel? What should I do?

I have written in Goodbye Junie Moon about my first marriage and how I lost my three children. How, knowing I could not have children, I decided to leave my husband and never marry again. It seemed to me that as an independent woman, there was no reason to marry if children were not the outcome. How could I tie down this wonderful young man and give him no sons? Besides, I still did not want to marry anyone. How then to let him down lightly? I had been in Vietnam a long while and I had seen the effects of ‘Dear John’ letters. I could not do that.

After much heartache I wrote back. I no longer remember my exact words but I did say that we should think about it a bit longer and get to know each other better. In my heart –I just did not want to hurt him. I knew we were mismatched. I had lived so much. He had lived so little (if you discount the daily stress of his job). I loved him but I wasn’t ‘in love’. And his proposal was no doubt influenced by the effects that the war was having on him.

I could envision him back in the USA with a lovely young girl, fresh from College, on his arm. One who could explore life with him. One who was ready to settle down and give him a family.

I drank a lot in those days. At first I drank for fun. Towards the end I drank from despair. Woody barely had a drink. No, it could never work!

I often wish I could remember the words I wrote in that letter. I hope they were gentle – not erasing all hope. I’m a sensitive person so I’m sure they were, but we all have moments of self doubt.

A few weeks later I received a letter from one of Woody’s mates. It was one who had had dinner with us at the Otani Hotel that night when I felt such a cold shiver.

The letter said Woody had been shot down over North Vietnam and he never had a chance to bail out.

Days of numbness- blackness,-mental turmoil.

Would my letter have arrived before that fatal mission? If not, would his parents have received it along with his belongings and read it?

All these years later…I still think of Woody and worry about that letter.

This is very interesting